Kafka DR: Why Replication Isn't the Hard Part

PagerDuty's 9-hour Kafka outage reveals the real DR problem - coordinating 47 services during crisis. Why replication alone won't save you.

On August 28, 2025, PagerDuty's Kafka cluster failed. The incident management platform that thousands of companies rely on to alert them about problems couldn't alert about its own problem.

The outage lasted over nine hours. At its peak, 95% of events were rejected. A logical error created 4.2 million extra Kafka producers per hour, overwhelming the brokers with metadata tracking overhead.

PagerDuty isn't a small startup learning Kafka. They run one of the most critical notification systems on the internet. And they still got bit.

If it can happen to them, it can happen to you.

The DR setup everyone has

Most organizations running Kafka in production have some version of disaster recovery in place. Two clusters in different regions. MirrorMaker 2 replicating topics and consumer offsets. Maybe Confluent Cluster Linking if you're on their platform.

The secondary cluster has the data. The replication lag is acceptable. Someone wrote a runbook. It lives in Confluence somewhere, probably last updated eight months ago.

The technical pieces are there. So why does DR still fail?

What actually happens during an outage

RTO breakdown

Let's break down what actually contributes to recovery time:

- Detection: 5-15 minutes. Assuming your alerting works and someone notices. PagerDuty's own status page updates were delayed during their outage because their automation also relied on the broken system.

- Coordination: 10-30 minutes. Finding the right people, getting approvals, figuring out the current state of things.

- Execution: Variable. If you need to update 47 services manually, you're looking at hours. If you have good automation, maybe minutes.

The "switch" itself might take seconds. Everything around it takes much longer.

What 3 hours of downtime actually costs

Technical teams measure outages in RTO and RPO. Executives measure them differently.

Revenue

A mid-size e-commerce processing $10M/day loses $1.25M in a 3-hour outage. That's before accounting for abandoned carts that never come back. For a fintech, 3 hours of blocked transactions means regulatory gaps and customers who move their money elsewhere.

Trust

PagerDuty published a transparent postmortem. Good. But how many of their customers started evaluating alternatives that week? Trust takes years to build and hours to destroy. Your next outage is someone else's sales opportunity.

Compliance

SOC 2 auditors will ask "show me your last DR test". If your answer is "we haven't tested it", that's a finding. If it took 3 hours, that's also a finding. PCI-DSS, HIPAA, and GDPR all have continuity requirements.

Reputation

When Kafka goes down, your customers don't see "Kafka". They see your product not working. They tweet about it. They post on LinkedIn. Your competitors don't need to be better. They just need to be up when you're not.

The core problem

Kafka isn't the problem. Kafka is doing exactly what it's supposed to do. When a cluster goes down, it goes down. That's what secondary clusters are for.

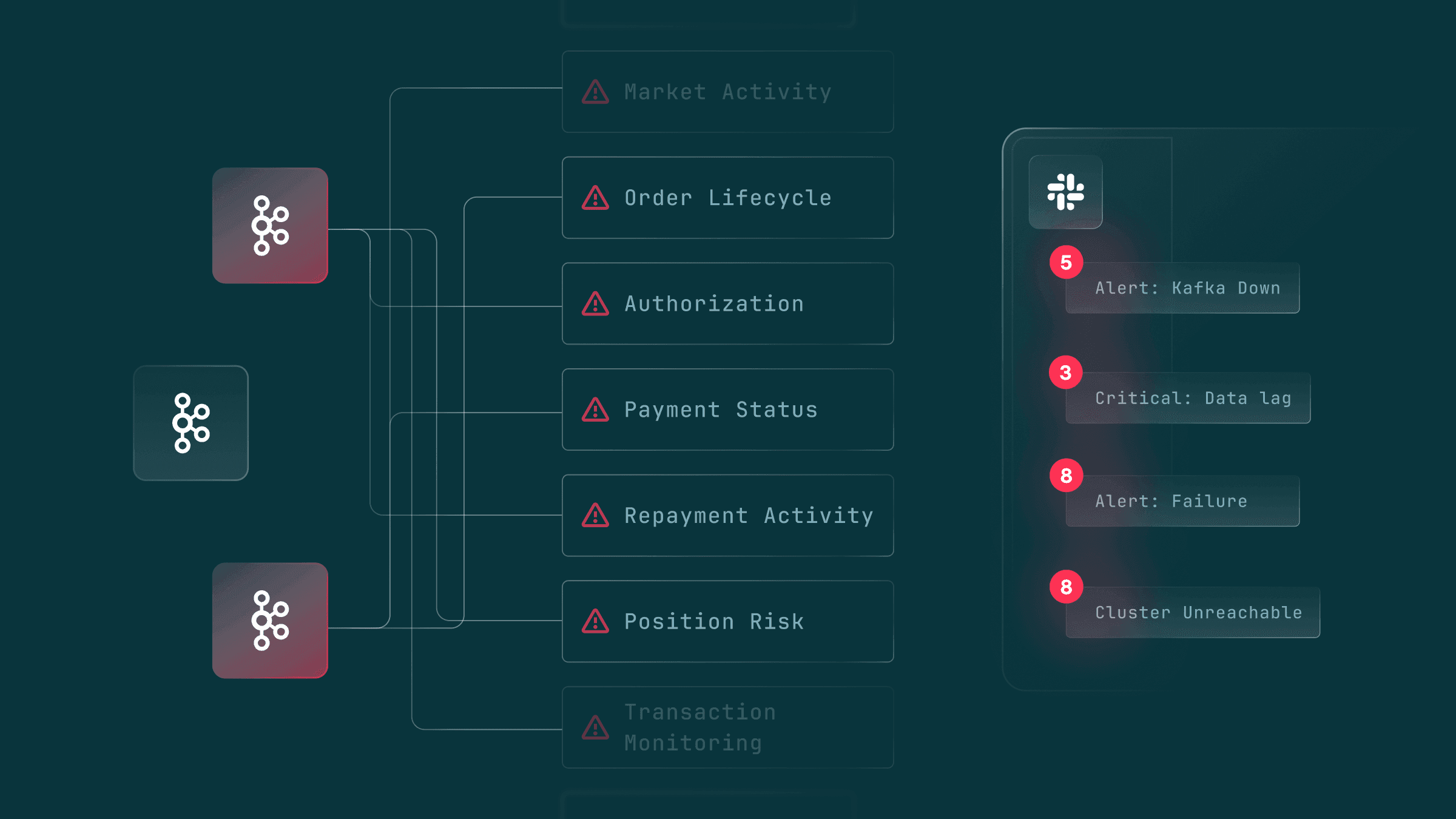

The problem is that failover requires touching many things simultaneously:

- Every producer needs new bootstrap servers

- Every consumer needs new bootstrap servers

- Credentials might be cluster-specific (Confluent Cloud API keys, for example)

- Config is scattered across services, repos, and teams

- No single team controls all of it

There's no single point where you can say "switch" and have everything follow.

What would fix this

The fix is a single endpoint for all Kafka clients. Not the brokers directly, but a proxy that knows about both your primary and secondary clusters. This is exactly what Conduktor Gateway provides.

When disaster hits, you switch at that single point. One API call. The proxy closes all client connections, and clients reconnect automatically. They don't know anything changed.

No scattered config updates. No coordinating across teams. No runbook with 23 steps.

The next incident is coming

Kafka will fail again. Not because Kafka is bad, but because distributed systems fail. The question is whether you'll spend 10 minutes recovering or 3 hours scrambling.

Your competitor's platform team might have figured this out last year. When the next regional outage hits, they'll be back online while you're still on a video call trying to find the runbook.

The best time to fix your DR architecture was before the last incident. The second best time is now.

Coming soon: how Gateway implements this, and what it doesn't do.

Want to see how Conduktor Gateway simplifies Kafka DR? Book a demo.