Saga Pattern for Distributed Transactions

In distributed systems and microservices architectures, managing transactions that span multiple services presents a fundamental challenge. Traditional ACID transactions don't scale across service boundaries, leading architects to adopt the Saga pattern as a proven alternative for maintaining data consistency in distributed environments.

What is the Saga Pattern?

The Saga pattern is a design pattern for managing distributed transactions by breaking them into a sequence of local transactions. Each local transaction updates data within a single service and publishes an event or message to trigger the next step in the saga. If any step fails, the saga executes compensating transactions to undo the changes made by preceding steps.

Unlike traditional distributed transactions that lock resources across multiple databases, sagas maintain consistency through eventual consistency and coordination. This approach trades immediate consistency for better availability and performance, aligning with the CAP theorem's practical constraints in distributed systems - in distributed architectures, you must choose between consistency and availability during network partitions, and sagas choose availability.

The pattern was first described in a 1987 paper by Hector Garcia-Molina and Kenneth Salem, but gained renewed relevance with the rise of microservices architecture in the 2010s.

The Problem with Distributed ACID Transactions

Traditional ACID transactions rely on two-phase commit (2PC) protocols to ensure atomicity across multiple databases. In 2PC, a coordinator first asks all participants to prepare (phase 1), then instructs them to commit if all agree (phase 2). While 2PC works in monolithic systems, it creates significant problems in microservices:

- Tight Coupling: Services must coordinate through a distributed transaction coordinator, creating dependencies that violate microservices principles.

- Reduced Availability: If any participating service is unavailable, the entire transaction cannot proceed. This contradicts the goal of building resilient, independently deployable services.

- Performance Bottlenecks: Locking resources across multiple services during the commit phase creates contention and reduces throughput.

- Scalability Limits: As the number of services grows, coordinating distributed locks becomes increasingly complex and fragile.

These limitations make 2PC unsuitable for modern cloud-native applications that prioritize availability and scalability over strict consistency.

Types of Saga Implementations

There are two primary approaches to implementing sagas: choreography and orchestration.

Choreography

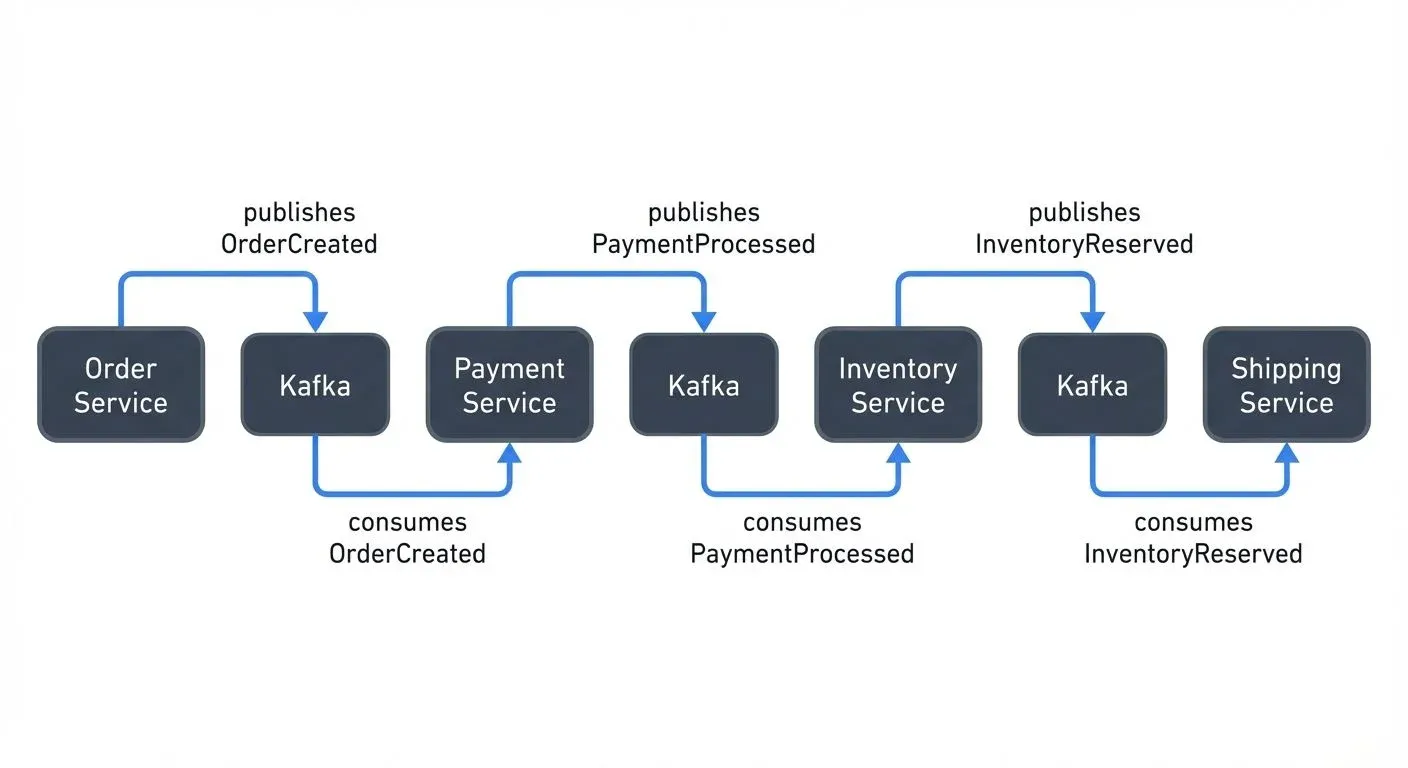

In choreographed sagas, each service produces and listens to events without a central coordinator. When a service completes its local transaction, it publishes an event that other services subscribe to.

Example: In an e-commerce order saga:

- Order Service creates an order and publishes

OrderCreatedevent - Payment Service listens for

OrderCreated, processes payment, publishesPaymentProcessed - Inventory Service listens for

PaymentProcessed, reserves items, publishesInventoryReserved - Shipping Service listens for

InventoryReservedand initiates delivery

Choreography is decentralized and follows event-driven architecture principles, but can become difficult to understand and debug as complexity grows. For more details on building systems with this pattern, see Event-Driven Microservices Architecture.

Orchestration

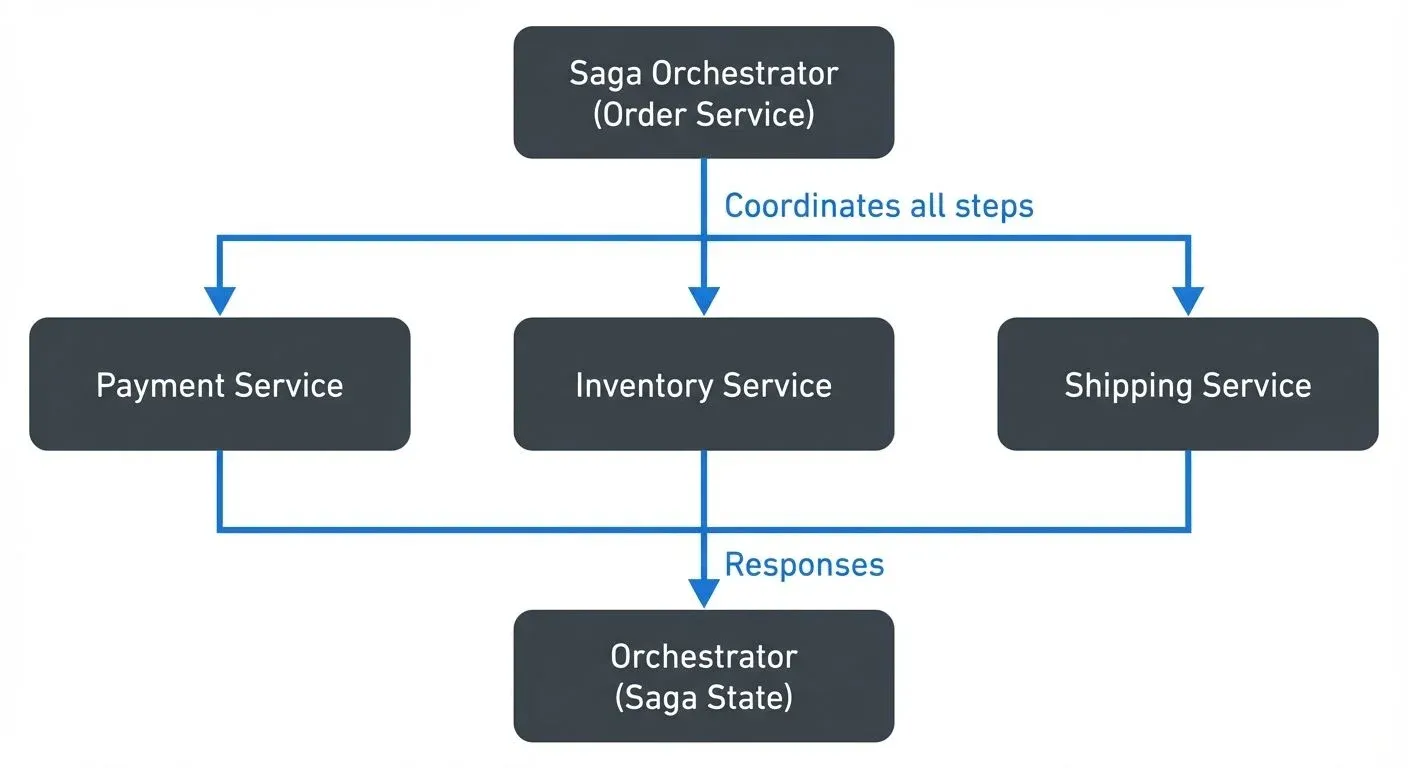

Orchestrated sagas use a central coordinator (the orchestrator) that tells each service what operation to perform. The orchestrator maintains the saga state and decides which step executes next.

Example: An Order Saga Orchestrator:

- Sends command to Payment Service: "Process payment for order #123"

- Waits for response

- Sends command to Inventory Service: "Reserve items for order #123"

- Sends command to Shipping Service: "Ship order #123"

Orchestration provides better visibility and easier testing, but introduces a potential single point of failure and can create coupling to the orchestrator service.

Saga Pattern in Event-Driven Architecture

The saga pattern fits naturally with event-driven architectures and streaming platforms like Apache Kafka. Kafka's distributed event log provides an ideal foundation for implementing choreographed sagas.

Each service in a saga can publish events to Kafka topics, and other services consume these events to trigger their local transactions. Kafka's durability guarantees ensure that events aren't lost, while its ordering guarantees within partitions help maintain saga sequencing.

Kafka-Based Saga Example

A choreographed saga using Kafka involves multiple services publishing and consuming events. Here's how an order saga works:

order-events topic: OrderCreated, OrderCancelled

payment-events topic: PaymentProcessed, PaymentFailed

inventory-events topic: InventoryReserved, InventoryUnavailableOrder Service (initiates the saga):

// Order Service publishes OrderCreated event

public void createOrder(Order order) {

orderRepository.save(order);

OrderCreatedEvent event = new OrderCreatedEvent(

order.getId(),

order.getCustomerId(),

order.getTotalAmount(),

UUID.randomUUID().toString() // correlation ID

);

kafkaTemplate.send("order-events", event.getOrderId(), event);

}Payment Service (reacts to OrderCreated):

@KafkaListener(topics = "order-events", groupId = "payment-service")

public void handleOrderCreated(OrderCreatedEvent event) {

try {

paymentProcessor.charge(event.getCustomerId(), event.getTotalAmount());

PaymentProcessedEvent successEvent = new PaymentProcessedEvent(

event.getOrderId(),

event.getCorrelationId()

);

kafkaTemplate.send("payment-events", event.getOrderId(), successEvent);

} catch (PaymentFailedException e) {

PaymentFailedEvent failureEvent = new PaymentFailedEvent(

event.getOrderId(),

event.getCorrelationId(),

e.getMessage()

);

kafkaTemplate.send("payment-events", event.getOrderId(), failureEvent);

}

}Order Service (compensates on failure):

@KafkaListener(topics = "payment-events", groupId = "order-service")

public void handlePaymentEvents(ConsumerRecord<String, Object> record) {

if (record.value() instanceof PaymentFailedEvent) {

PaymentFailedEvent event = (PaymentFailedEvent) record.value();

// Compensate by canceling the order

Order order = orderRepository.findById(event.getOrderId());

order.setStatus(OrderStatus.CANCELLED);

orderRepository.save(order);

OrderCancelledEvent cancelEvent = new OrderCancelledEvent(

event.getOrderId(),

event.getCorrelationId(),

"Payment failed: " + event.getReason()

);

kafkaTemplate.send("order-events", event.getOrderId(), cancelEvent);

}

}Each service consumes from relevant topics and produces to its own topic. Correlation IDs embedded in events link related transactions across the saga workflow, enabling distributed tracing and debugging.

While stream processing frameworks like Apache Flink or Kafka Streams can maintain saga state and coordinate event flows, production systems typically benefit from purpose-built saga orchestration tools designed specifically for distributed transaction management (discussed in the Modern Saga Orchestration Tools section below).

When implementing sagas with Kafka, visibility into event flows becomes critical. Streaming governance tools help teams monitor saga execution by visualizing event flows across topics, tracking correlation IDs, and identifying stuck or failed sagas through data lineage features.

Modern Saga Orchestration Tools (2025)

While choreographed sagas can be built directly on Kafka, orchestrated sagas benefit from specialized workflow engines that provide saga state management, timeout handling, and compensation coordination out of the box. As of 2025, several mature tools have emerged:

Temporal: A durable execution platform that treats sagas as long-running workflows. Temporal provides automatic retries, timeout management, and versioning. Workflows are written in regular code (Go, Java, TypeScript, Python) and Temporal handles durability and fault tolerance.

// Temporal saga example

@WorkflowInterface

public interface OrderSagaWorkflow {

@WorkflowMethod

OrderResult processOrder(Order order);

}

public class OrderSagaWorkflowImpl implements OrderSagaWorkflow {

private final Activities activities = Workflow.newActivityStub(Activities.class);

@Override

public OrderResult processOrder(Order order) {

try {

activities.processPayment(order.id);

activities.reserveInventory(order.id);

activities.shipOrder(order.id);

return OrderResult.success();

} catch (Exception e) {

// Temporal automatically handles compensation

Saga.compensate(() -> activities.refundPayment(order.id));

Saga.compensate(() -> activities.releaseInventory(order.id));

return OrderResult.failed(e.getMessage());

}

}

}- Camunda 8: Cloud-native workflow orchestration using BPMN diagrams. Camunda 8 excels at visualizing complex saga flows and integrates with Kafka through connectors. The visual workflow designer helps teams document and communicate saga logic.

- Dapr Workflows: Part of the CNCF's Distributed Application Runtime project, Dapr provides language-agnostic saga orchestration. Dapr workflows integrate seamlessly with Dapr's pub/sub and state management building blocks, making it ideal for Kubernetes environments.

- AWS Step Functions: For AWS-based systems, Step Functions provides serverless saga orchestration with visual workflow editing. Step Functions integrates natively with Lambda, SQS, and EventBridge, though it's limited to AWS infrastructure.

- Choosing an Orchestration Tool: Select based on your infrastructure (cloud vs on-prem), team skills (prefer code-first or visual design), and existing tech stack. Temporal and Dapr offer the most flexibility, while Camunda excels at complex workflow visualization and Step Functions works best for AWS-native architectures.

Compensation and Rollback Strategies

Unlike database transactions that rollback on failure, sagas use compensating transactions to semantically undo completed steps. This is a crucial distinction: compensating transactions don't restore the database to its exact previous state, but rather logically reverse the business operation.

Designing Compensating Transactions

Each saga step must have a corresponding compensating transaction:

- ReserveInventory ↔ ReleaseInventory

- ChargeCustomer ↔ RefundCustomer

- SendConfirmationEmail ↔ SendCancellationEmail

Compensating transactions must be:

Idempotent: Running the same compensation multiple times produces the same result, handling duplicate messages gracefully. For example, "RefundCustomer $50" should check if a refund was already issued - running it twice shouldn't refund $100. Implement idempotency using:

- Unique transaction IDs stored in the database

- Conditional updates (UPDATE ... WHERE status != 'REFUNDED')

- Idempotency keys in payment APIs

// Idempotent refund compensation

public void refundCustomer(String orderId, String compensationId) {

// Check if already compensated

if (compensationRepository.exists(compensationId)) {

return; // Already processed, skip

}

paymentService.refund(orderId);

compensationRepository.save(new Compensation(compensationId, orderId));

}- Semantically Correct: The compensation reverses the business effect, even if it doesn't restore exact database state. A refund creates a new transaction rather than deleting the original charge - the effect (customer balance) is restored, but the history remains.

- Always Possible: Unlike rollbacks, compensations can't always be executed (you can't un-send an email), requiring careful design of saga boundaries. Design sagas so irreversible actions happen at the end, after all fallible steps complete.

Failure Scenarios and Recovery Strategies

When a saga step fails, you have two recovery options: backward recovery (compensation) or forward recovery (retry). Choosing the right strategy depends on the failure type.

Backward Recovery (Compensation): When a saga step fails, the saga coordinator (in orchestration) or the failing service (in choreography) triggers compensating transactions in reverse order. This ensures that completed steps are undone before the saga terminates. Use compensation for:

- Business rule violations (insufficient inventory, credit limit exceeded)

- Permanent failures (invalid data, authorization denied)

- Steps that cannot be retried safely

Forward Recovery (Retry): Instead of compensating, the saga retries failed steps until they succeed. Modern distributed systems increasingly favor forward recovery because:

- Transient failures (network glitches, temporary service unavailability) are more common than permanent failures

- Retries are simpler to implement and reason about than compensation

- Many cloud services have built-in retry mechanisms

Best practice in 2025: Implement hybrid recovery - retry transient failures with exponential backoff, then compensate only if retries exhaust or the failure is permanent. Modern saga orchestrators like Temporal handle this automatically:

// Temporal hybrid recovery

ActivityOptions options = ActivityOptions.newBuilder()

.setStartToCloseTimeout(Duration.ofMinutes(5))

.setRetryOptions(RetryOptions.newBuilder()

.setMaximumAttempts(3)

.setBackoffCoefficient(2.0)

.build())

.build();

// Temporal retries automatically; compensation only runs if all retries failDeciding Between Choreography and Orchestration: Choose based on these factors:

| Factor | Choreography | Orchestration |

|---|---|---|

| Complexity | Simple, linear flows (2-4 steps) | Complex flows with branching, loops |

| Visibility | Distributed across services | Centralized in orchestrator |

| Coupling | Loosely coupled | Services coupled to orchestrator |

| Testing | Requires integration tests | Can test orchestrator logic in isolation |

| Team Structure | Independent teams owning services | Central platform team possible |

| Debugging | Harder - need distributed tracing | Easier - single point of observability |

| Evolution | Changes require multiple service updates | Changes centralized in orchestrator |

Real-World Implementation Considerations

Implementing sagas in production requires attention to several practical concerns:

State Management

Saga state must be persisted to survive service restarts. In orchestrated sagas, the orchestrator maintains state in a database. In choreographed sagas, each service tracks its own state using techniques like event sourcing.

Outbox Pattern for Reliable Publishing: When a saga step needs to atomically update local state and publish an event, use the Outbox Pattern to avoid the dual-write problem. This ensures saga events are always published, even if the message broker is temporarily unavailable.

Timeouts and Deadlines

Sagas can't wait indefinitely for responses. Implement timeouts for each step, triggering compensation when deadlines expire. This prevents sagas from hanging indefinitely due to failed services.

Isolation Challenges

Sagas lack the isolation guarantees of ACID transactions. Intermediate states are visible to other transactions, potentially causing anomalies like dirty reads. For example, if a saga reserves inventory but later fails and compensates, another customer might see "low stock" warnings based on the temporary reservation.

Techniques to mitigate isolation issues:

Semantic Locks: Mark records with a "pending" or "in-progress" status to signal to other transactions that the entity is involved in an incomplete saga. For example, set order status to "PENDING" during the saga, only changing to "CONFIRMED" when complete.

// Other services check status before acting

if (order.getStatus() == OrderStatus.PENDING) {

// Don't process - saga still in progress

return;

}- Version Numbers (Optimistic Locking): Detect conflicts when multiple sagas operate on the same data. Each update increments a version number; if a saga tries to update stale data, it fails and compensates.

- Commutative Operations: Design operations that produce the same result regardless of order. For example, "add $10 to account balance" and "add $5 to account balance" are commutative - they work in any order. This reduces the need for strict ordering in choreographed sagas.

Monitoring and Debugging

Distributed sagas are harder to debug than monolithic transactions. A saga spans multiple services, databases, and message queues, making it difficult to understand what happened when failures occur.

- Essential Observability Practices:

- Correlation IDs: Embed a unique saga ID in every event and log message. This allows you to trace all operations belonging to a single saga instance across services.

- Distributed Tracing: Use OpenTelemetry or Jaeger to visualize saga execution flow. Create spans for each saga step, showing timing, dependencies, and where failures occurred. Modern tracing tools can correlate Kafka message flows with service operations.

// OpenTelemetry span for saga step

Span span = tracer.spanBuilder("process-payment")

.setAttribute("saga.id", sagaId)

.setAttribute("order.id", orderId)

.startSpan();

try {

paymentService.processPayment(orderId);

} finally {

span.end();

}- Saga State Visualization: For orchestrated sagas, expose the current state via APIs or dashboards. Tools like Temporal provide built-in UI showing which sagas are running, stuck, or failed.

- Event Stream Monitoring: For Kafka-based sagas, platforms like Conduktor provide visibility into event flows, helping teams track saga progress, identify stuck sagas through consumer lag monitoring, and validate event schemas to prevent deserialization errors.

Testing

Test sagas under failure conditions: what happens when step 3 of 5 fails? Simulate service unavailability, network partitions, and timeouts to verify compensating logic works correctly.

Troubleshooting Common Saga Issues

When sagas fail in production, diagnose and resolve issues using these approaches:

Saga Stuck in Progress: If a saga appears hung with no progress:

- Check consumer lag - services may be down or overloaded

- Verify timeout configuration - missing timeouts cause indefinite waits

- Review distributed traces to find which step never completed

- Check for poison messages preventing consumer progress

Compensation Not Triggered: If failures don't trigger rollback:

- Verify error handling catches all exception types

- Check that compensating transactions are registered before execution

- Review logs for silent failures that don't bubble up

- Ensure idempotency keys prevent duplicate compensation

Saga Completes But State Inconsistent: When the saga "succeeds" but data is wrong:

- Check for race conditions - concurrent sagas modifying same data

- Verify isolation controls (semantic locks, version numbers)

- Review eventual consistency windows - reads may hit stale replicas

- Validate event ordering - Kafka partition keys ensure related events stay ordered

Duplicate Saga Execution: Same saga runs multiple times:

- Implement idempotency checks at saga initiation

- Use unique saga IDs and check for duplicates before starting

- Review producer retry settings - ensure exactly-once semantics

- Check for message replay after consumer rebalances

How to Recover: When sagas fail partially:

- Query saga state to determine current step

- Decide: retry forward or compensate backward

- For stuck sagas, manually trigger timeout or compensation

- Use saga orchestrator's admin API (Temporal UI, Camunda Cockpit) for manual intervention

- Document incident for postmortem - adjust timeouts or add circuit breakers

Summary

The Saga pattern provides a practical approach to distributed transactions in microservices architectures, trading strict ACID guarantees for better availability and scalability. By decomposing transactions into local operations with compensating actions, sagas enable consistent business operations across service boundaries.

Choosing between choreography and orchestration depends on your system's complexity, team structure, and visibility requirements. Choreographed sagas align well with event-driven architectures and streaming platforms like Kafka, while orchestrated sagas offer clearer workflow visibility at the cost of centralization.

Successful saga implementation requires careful attention to compensation logic, idempotency, timeout handling, and monitoring. When built on event streaming platforms, tools that provide visibility into event flows and data lineage become essential for operating sagas reliably in production.

The saga pattern isn't a universal solution, simple workflows within service boundaries should still use local ACID transactions. But for complex, cross-service business processes in distributed systems, sagas represent the current best practice for maintaining consistency without sacrificing availability.

Related Concepts

- Outbox Pattern for Reliable Event Publishing - Ensuring atomic database updates and event publishing within saga steps

- Event-Driven Microservices Architecture - Architectural foundation for choreographed sagas

- Exactly-Once Semantics - Ensuring data consistency in saga workflows

Related Patterns and Further Reading

Sagas work best when combined with complementary distributed system patterns:

- Outbox Pattern: Ensures atomic database updates and event publishing within each saga step, solving the dual-write problem.

- CQRS and Event Sourcing: Event sourcing naturally complements sagas by providing complete audit trails and the ability to rebuild state from events.

- Event-Driven Microservices: Provides the architectural foundation for choreographed sagas using asynchronous event communication.

- Distributed Tracing: Essential for debugging and monitoring saga execution across multiple services.

Sources and References

- Garcia-Molina, H., & Salem, K. (1987). "Sagas." ACM SIGMOD Record, 16(3), 249-259. [Original academic paper introducing the saga pattern]

- Richardson, C. (2018). "Microservices Patterns: With Examples in Java." Manning Publications. [Comprehensive coverage of saga patterns in microservices, including implementation details]

- Fowler, M. (2015). "Event Sourcing." martinfowler.com. [Context on event-driven architectures that complement saga implementations]

- Kleppmann, M. (2017). "Designing Data-Intensive Applications." O'Reilly Media. [Chapter 9 covers distributed transactions and consensus, providing theoretical foundation]

- Stopford, B. (2018). "Designing Event-Driven Systems." O'Reilly Media. [Practical guide to implementing sagas with Apache Kafka and event streaming]

Written by Stéphane Derosiaux · Last updated February 11, 2026