What is Real-Time Data Streaming?

For decades, organizations processed data in batches, collecting information throughout the day and running analytics jobs overnight or at scheduled intervals. While batch processing remains useful for many scenarios, modern businesses increasingly need to react to events as they happen.

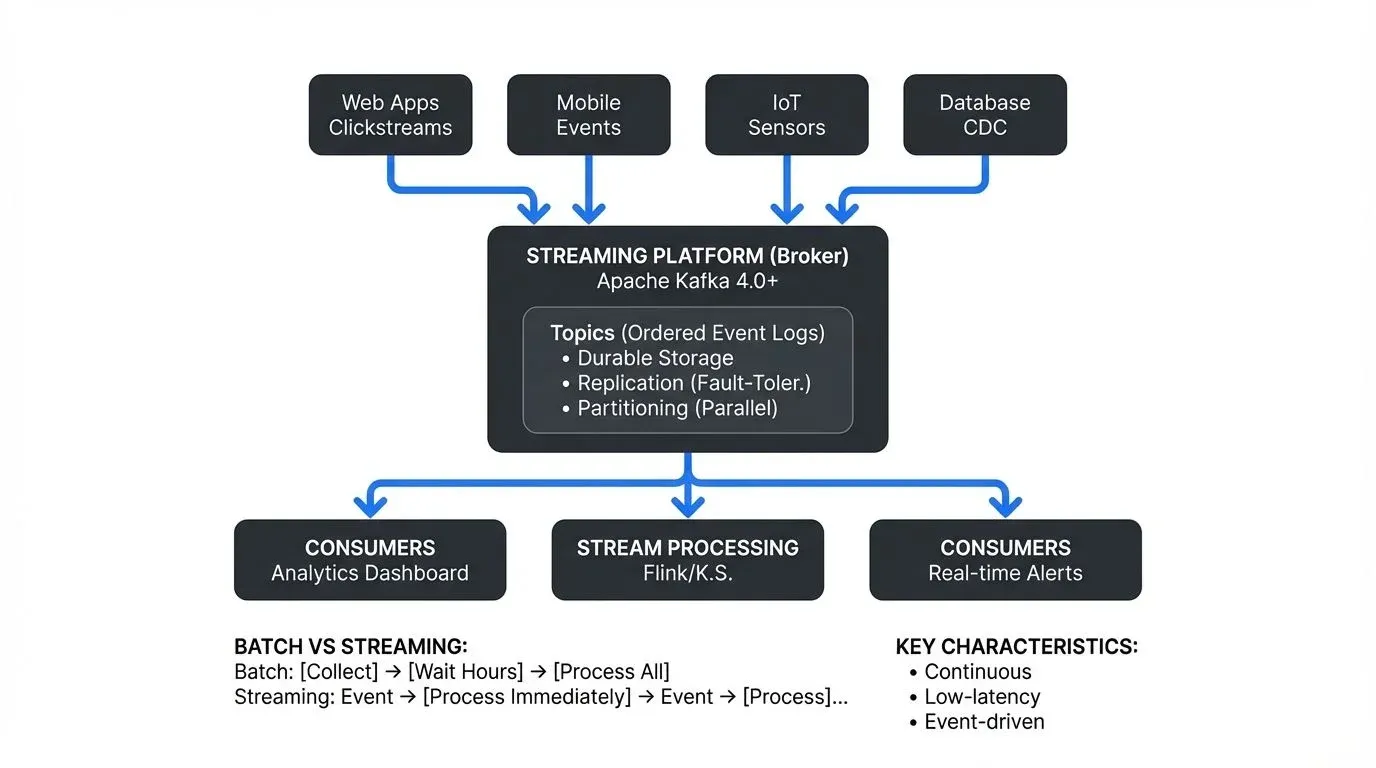

Real-time data streaming represents a fundamental shift in how we handle data. Instead of waiting for scheduled batch jobs, streaming systems process data continuously as it arrives, enabling organizations to detect fraud within milliseconds, personalize user experiences instantly, and monitor infrastructure in real-time.

This article explores what real-time data streaming is, how it works, and why it has become a cornerstone of modern data architectures.

Understanding Real-Time Data Streaming

Streaming vs Batch Processing

Batch processing collects data over a period and processes it as a single unit. For example, a retail system might aggregate all daily transactions and generate reports at midnight. This approach works well when timeliness isn't critical and processing large volumes together is more efficient.

Streaming processing, by contrast, treats data as a continuous flow of events. Each transaction, click, sensor reading, or log entry is processed individually or in small micro-batches as it occurs. This enables near-instantaneous responses and continuous analytics.

Core Concepts

- Events are the fundamental unit in streaming systems. An event represents something that happened, a user clicked a button, a sensor reported a temperature, or a payment was processed. Events are immutable facts about what occurred at a specific point in time.

- Streams are unbounded sequences of events. Unlike static datasets with a clear beginning and end, streams are continuous and potentially infinite. A stream might represent all clicks on a website, all temperature readings from IoT sensors, or all transactions in a payment system.

- Producers are applications or systems that generate events and publish them to streams. A mobile app tracking user behavior, an IoT device sending sensor data, or a database capturing changes are all producers.

- Consumers are applications that read events from streams and process them. A fraud detection system analyzing transactions, an analytics engine computing real-time metrics, or a data warehouse ingesting events for long-term storage are all consumers.

- Brokers are the infrastructure components that receive events from producers, store them durably, and serve them to consumers. Brokers handle the complexity of distributed storage, replication, and delivery guarantees.

Key Technologies and Platforms

Several technologies have emerged as leaders in the real-time streaming space.

- Apache Kafka is the most widely adopted streaming platform. Originally developed at LinkedIn, Kafka provides a distributed, fault-tolerant broker system that can handle millions of events per second. With Kafka 4.0+ (2024), the platform operates entirely on KRaft consensus (replacing ZooKeeper), providing improved scalability, faster cluster recovery, and simplified operations. For detailed coverage of this architecture shift, see Understanding KRaft Mode in Kafka. Kafka stores streams as ordered logs and allows multiple consumers to read at different speeds without affecting each other. Kafka's ecosystem includes Kafka Streams and ksqlDB for stream processing.

- Apache Flink is a stream processing framework designed for stateful computations over unbounded and bounded datasets. Flink 1.18+ (2024-2025) brings enhanced SQL capabilities, improved Python API support, and unified batch-streaming execution. Flink excels at complex event processing, windowing operations, and maintaining exactly-once processing semantics. It can process streams with low latency while handling state management and fault tolerance automatically. For comprehensive coverage, see What is Apache Flink: Stateful Stream Processing.

- Apache Pulsar is a cloud-native messaging and streaming platform that separates compute from storage, offering multi-tenancy and geo-replication out of the box. Pulsar combines messaging patterns with streaming capabilities in a unified architecture.

- Cloud-native services like AWS Kinesis, Azure Event Hubs, and Google Cloud Pub/Sub provide managed streaming infrastructure without the operational overhead of running your own clusters. These services integrate seamlessly with other cloud offerings, making it easier to build end-to-end streaming pipelines.

- Stream processing frameworks transform and analyze data in motion. Kafka Streams (integrated with Kafka 4.0+) provides a lightweight Java library for processing streams with stateful operations, windowing, and joins, no separate cluster required. For an introduction, see Introduction to Kafka Streams. ksqlDB enables SQL queries on Kafka streams, making stream processing accessible to SQL-familiar developers. These frameworks handle the complexity of stateful computations, time-based windowing, and exactly-once processing semantics.

Real-World Use Cases

Real-time streaming solves problems that batch processing cannot address effectively.

- Fraud detection requires analyzing transactions as they occur. Financial institutions use streaming to evaluate each payment against behavioral patterns, detect anomalies, and block fraudulent transactions before they complete. Waiting for a nightly batch job would allow fraud to succeed undetected.

- IoT monitoring involves processing massive volumes of sensor data from devices, vehicles, or industrial equipment. Streaming enables predictive maintenance by identifying equipment failures before they occur, optimizing energy consumption in real-time, and alerting operators to dangerous conditions immediately.

- Clickstream analytics captures how users interact with websites and applications. Companies stream click events to understand user behavior, personalize content dynamically, run A/B tests, and optimize conversion funnels based on live traffic patterns.

- Change Data Capture (CDC) streams database changes to other systems. When a customer updates their address in one database, CDC can propagate that change to data warehouses, search indexes, caches, and other applications in real-time, keeping data synchronized across the organization. For comprehensive coverage, see What is Change Data Capture (CDC): Fundamentals.

- Real-time recommendations power personalization engines that adapt to user behavior instantly. Streaming services suggest content based on what you're watching right now, e-commerce sites recommend products based on your current browsing session, and social media platforms curate feeds based on recent interactions.

Benefits and Challenges

Benefits

- Low latency is the primary advantage of streaming. Events are processed within milliseconds or seconds of occurring, enabling immediate responses and real-time decision making. This speed is impossible with batch processing.

- Continuous processing means systems are always active and up-to-date. There are no gaps between batch runs where data sits waiting to be processed. Analytics dashboards show current state, not yesterday's snapshot.

- Event-driven architectures built on streaming decouple systems through asynchronous communication. Services publish events without knowing who will consume them, making systems more flexible and easier to evolve. New consumers can be added without modifying producers.

Challenges

- Complexity increases with streaming systems. Distributed architectures, stateful processing, and handling failures across multiple components require different skills than traditional batch ETL. Teams need expertise in stream processing frameworks and distributed systems.

- Exactly-once semantics is difficult to achieve. Ensuring each event is processed once and only once, even when systems fail and restart, requires careful design and coordination between producers, brokers, and consumers. For example, if a consumer processes a payment event and crashes before committing its offset, the event might be processed twice on restart, potentially double-charging a customer. Many systems settle for at-least-once delivery, requiring idempotent processing logic to handle duplicates safely. For detailed coverage of achieving exactly-once processing, see Exactly-Once Semantics in Kafka.

- State management becomes challenging when processing streams. Computing aggregations, joins, or complex patterns requires maintaining state across many events. For example, calculating a 30-day rolling average of user activity requires storing activity counts for each user and updating them as new events arrive. This state must be durable, consistent, and capable of being recovered after failures. For Flink's approach to state management, see Flink State Management and Checkpointing.

- Ordering guarantees are not universal. While individual partitions in systems like Kafka maintain order, processing events across partitions or in distributed consumers can result in out-of-order processing. Applications must decide whether strict ordering is necessary and design accordingly.

A Concrete Example: E-commerce Order Processing

To illustrate how streaming works in practice, consider an e-commerce platform processing orders in real-time:

- Event Generation: When a customer clicks "Buy Now", the web application (producer) publishes an "OrderPlaced" event to a Kafka topic containing order details, customer ID, and timestamp.

- Event Storage: Kafka brokers receive the event, replicate it across multiple servers for durability, and make it available to consumers. The event is stored in an ordered log within a topic partition.

- Parallel Processing: Multiple consumers process the same event for different purposes, a fraud detection service analyzes the order for suspicious patterns, an inventory service reserves products, a recommendation engine updates the customer's profile, and an analytics pipeline computes real-time sales metrics.

- Real-time Response: If fraud detection flags the order within milliseconds, the payment service receives a "HoldPayment" event before charging the card. Meanwhile, the customer sees real-time order status updates based on events flowing through the system.

This event-driven flow enables each service to react independently while maintaining a consistent view of what's happening across the organization.

Streaming in Modern Data Architectures

Real-time streaming has become integral to modern data architectures, connecting transactional systems, analytical workloads, and operational applications.

- Lakehouse architectures combine the flexibility of data lakes with the structure of data warehouses. Streaming feeds both operational analytics and batch processing. Modern lakehouse table formats like Apache Iceberg 1.5+, Delta Lake 3.0+, and Apache Paimon enable streaming ingestion with ACID transactions, time travel, and schema evolution. For detailed coverage of lakehouse concepts, see Introduction to Lakehouse Architecture and Apache Iceberg. These formats provide exactly-once ingestion from Kafka and Flink, enabling unified batch and streaming analytics on the same tables.

- Data mesh architectures treat data as a product owned by domain teams. Streaming provides the real-time data pipelines that connect domain-owned data products. Events flow between domains through well-defined interfaces, enabling decentralized data ownership while maintaining integration. For implementation guidance, see Data Mesh Principles and Implementation.

- Event-driven architectures use streaming platforms as the nervous system of the organization. Applications communicate through events rather than direct API calls, reducing coupling and enabling better scalability. The event stream becomes a shared log of everything that has happened, providing a foundation for event sourcing and audit trails. For architectural patterns, see Event-Driven Architecture and Event Sourcing Patterns with Kafka.

Observability and Monitoring

As streaming systems grow in complexity, observability becomes essential for understanding system health and performance. Modern streaming observability combines metrics, logs, and traces to provide comprehensive visibility.

- Consumer lag monitoring tracks how far behind consumers are in processing events. Tools like Kafka Lag Exporter (2024+) export consumer lag metrics to Prometheus, enabling alerting when consumers fall behind. For detailed coverage, see Consumer Lag Monitoring. Monitoring lag helps identify performance bottlenecks, capacity issues, or failing consumers before they impact business operations.

- Distributed tracing with OpenTelemetry provides end-to-end visibility across streaming pipelines. Traces follow events from producers through brokers to consumers, revealing latency hotspots and performance degradation. For comprehensive tracing strategies, see Distributed Tracing for Kafka Applications.

- Data quality observability monitors streaming data for anomalies, schema violations, and data freshness issues. Platforms track data quality metrics in real-time, alerting teams to incidents before they propagate downstream. For foundational concepts, see What is Data Observability: The Five Pillars.

Governance and Visibility

As streaming infrastructure grows, governance becomes critical. Organizations need visibility into what data flows through their systems, who has access, and whether sensitive information is handled correctly.

This is where platforms like Conduktor help. Managing hundreds of topics, thousands of schemas, and complex access control policies across streaming infrastructure requires specialized tooling. Governance platforms provide centralized visibility into streaming data, enforce access controls, monitor data quality, and ensure compliance with regulations. Teams can use self-service workflows to request and manage Kafka topics without sacrificing security or creating data silos. For security best practices, see Access Control for Streaming.

Getting Started with Data Streaming

Teams considering real-time streaming should evaluate several factors before diving in.

- Infrastructure choices come first. Decide whether to run open-source platforms like Kafka and Flink on your own infrastructure, use managed cloud services, or adopt a hybrid approach. Consider operational expertise, cost, and integration with existing systems.

- Skill requirements differ from batch processing. Stream processing requires understanding event time vs processing time, windowing, watermarks, and stateful computations. Invest in training or hire engineers with streaming experience.

- Use case selection matters for initial success. Start with a clear, valuable use case rather than trying to stream everything. Look for scenarios where low latency provides tangible business value, fraud detection, real-time personalization, or operational monitoring are good candidates.

- Governance setup should not be an afterthought. Establish naming conventions, access control policies, schema management, and monitoring before your streaming infrastructure scales. Setting up governance early prevents the chaos that emerges when hundreds of teams are producing and consuming streams without coordination.

- Schema management is essential for maintaining compatibility as systems evolve. Use schema registries to enforce contracts between producers and consumers, enable schema evolution without breaking consumers, and document what data flows through your systems. For schema format comparisons, see Avro vs Protobuf vs JSON Schema.

Summary

Real-time data streaming has transformed how organizations handle data, enabling immediate responses to events and powering modern data architectures. Unlike batch processing, streaming treats data as continuous flows of events processed as they occur.

Core concepts include events, streams, producers, consumers, and brokers. Technologies like Apache Kafka, Apache Flink, and Apache Pulsar provide the infrastructure for building streaming systems, while cloud services offer managed alternatives.

Streaming enables use cases impossible with batch processing, fraud detection, IoT monitoring, clickstream analytics, change data capture, and real-time recommendations. Benefits include low latency, continuous processing, and event-driven architectures, though challenges exist around complexity, exactly-once semantics, state management, and ordering.

Streaming fits naturally into modern data architectures like lakehouses and data mesh, serving as the real-time backbone connecting systems. Success requires careful consideration of infrastructure, skills, use cases, and governance.

Organizations that master real-time data streaming gain a competitive advantage through faster insights, better customer experiences, and more responsive operations.

Related Concepts

- Apache Kafka - The most widely adopted distributed streaming platform

- What is Apache Flink: Stateful Stream Processing - Stream processing framework for complex event processing

- Exactly-Once Semantics in Kafka - Achieving reliable message processing guarantees

Sources and References

- Apache Kafka Documentation - https://kafka.apache.org/documentation/

- Akidau, Tyler, et al. "Streaming Systems: The What, Where, When, and How of Large-Scale Data Processing." O'Reilly Media, 2018.

- Apache Flink Documentation - https://flink.apache.org/

- Confluent Blog - https://www.confluent.io/blog/

- AWS Kinesis Documentation - https://aws.amazon.com/kinesis/

- Azure Event Hubs Documentation - https://azure.microsoft.com/en-us/services/event-hubs/

- Narkhede, Neha, et al. "Kafka: The Definitive Guide." O'Reilly Media, 2017.

Written by Stéphane Derosiaux · Last updated February 11, 2026